or: How they Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Internet

It is my opinion that Autodesk is in the early stages of implementing a bold Internet-centric strategy that if successful will position it as the Software + Services giant within the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industry. Excluding the spin-off and re-purchase of Buzzsaw during the Dot-com bubble one could say Autodesk's attitude towards the Web, like the rest of the AEC industry, has been tepid at the best. In a similar manner to Microsoft, the historical and financial foundations of Autodesk lie in the traditional, desktop software market. Here its catalogue of heavy-weight tools compete for domination of the competitive CAD, BIM, animation and rendering markets. Unlike Microsoft vs Google, Autodesk and its competitors (such as Bentley Systems) have yet to face serious competition from an Internet savvy, AEC software heavy-weight. Rather than waiting for such a competitor to emerge Mike Haley, Jeff Wright and the rest of Autodesk's Content division are building it 'in-house'.

The goal: building really big 3D models in the cloud

AEC software vendors have largely ignored the Internet and have been content to focus on what can be done on a single workstation. The problem is that simultaneously other industries have demonstrated what is possible on the network, for example virtual worlds and photo-realistic visual experiences. Hence as our expectations have grown we are finding a single workstation cannot hope to keep up with these perpetually increasing processing demands. Consequently at some point the AEC software industry must make the step from tried and true desktop CAD/BIM to the less understood, but potentially more capable platform now referred to as cloud computing.

But why are really big, 3D models important in the eyes of industry professionals and public? The answer is simple, architecture is not mass production and the first time a design gets built is generally the last. From the perspective of understanding the design and its issues this is not ideal as the shift from the abstract to real world almost never happens painlessly. Not only is there design problems, for example 'does the detailing of the design match the overall aesthetic and its surroundings?', but there are also performance questions such as 'what are the temperature and light qualities like in the lounge in late winter when the sun goes behind the building across the road?'. The ability to digitally realise the entire design - from the exact detailing of its window frames to its geographic context, enables those involved to 'virtually' build and experience the architecture in a very cost effective manner.

At this point many will be thinking, isn't this what I do in Revit, Microstation or ArchiCAD every day? The answer is yes, but on a scale that is almost impossible to fathom. At this level it is not just about what you as a single person can record about a model, but rather the bringing together of vast quantities of data from multiple sources in order for it to be experienced in one place and time.

An outsiders overview of the strategy

Whilst I have recently spoken with Mike Haley and Abhi Singh from Autodesk about Seek and their evolving Internet strategy, what follows is primarily my own summary of the bigger picture drawn from the thoughts of some of those involved. Expect to hear and see more definitive things from Autodesk during the course of the year, especially at December's Autodesk Univserity.

Note: Buzzsaw is not included in this discussion as it is a closed tool that is not widely available on the Internet (i.e. it conforms to the classical notion of the closed, corporate Intranet).

Autodesk's Internet strategy is driven by the Content division within Autodesk. The goal of the strategy is to harness the potential of Internet-centric infrastructure to scale beyond that considered possible on the desktop or traditional corporate network. With the efficient scaling of digital infrastructure comes the ability to push the boundaries of the digital model - not only in its scope and depth of detail, but also in the designer's ability to simulate its properties.

The infrastructure for achieving this goal has been broken down into four distinct functional components as illustrated by the diagram below.

Whilst each functional component is at a different stage of development, aspects of each have been demonstrated to the public in some way, shape or form:

- Seek - Product and material index: http://seek.autodesk.com/

- Dragonfly - Web-centric modelling: http://labs.autodesk.com/technologies/draw/

- Showroom - Render-wall service: http://labs.autodesk.com/technologies/showroom/

- Metropolis - Massive 3D environment space: Autodesk University demo video

Individually these projects break a little new ground, but when viewed as an integrated suite of cloud-based services their true potential becomes apparent. Together the four services form a platform that if successfully implemented, may revolutionise the way AEC professionals conceive, produce and experience digital models.

Seek

Seek is a sophisticated data conduit for architectural information. I have covered Seek previously and Mike Haley has an even better video presentation. The intention behind Seek is to build an index of architectural details and materials, their associated meta-data and any digital files which maybe associated to them (e.g. DWG and PDF files). Unlike a supplier-centric materials index, Seek's primary motive is to facilitate information sharing amongst architectural suppliers and professionals. The intention is that this data-store can be leveraged to help construct more precise 3D models, add richness to renderings and provide material performance data for thermal simulations.

Metropolis

Metropolis is the bridging of virtual world concepts (a.k.a Google Earth) and serious 3D modelling. Rather than focusing on the macro OR the micro the emphasis of Metropolis is to create a virtual space capable of handling everything from the planet down to a pencil. The challenge this project is attempting to overcome is how to efficiently retrieve and process massive amounts of 3D data. Whilst the technical barriers are huge, if they can be surmounted being able to quickly visualise fully furnished, architectural designs within their actual geographic context is a real possibility.

Dragonfly

Dragonfly is attempting to bring CAD concepts to the cloud computing environment. The intention of Dragonfly is not to recreate AutoCAD or Revit within the Internet browser, but to leverage this ubiquitous platform to deliver and manipulate 3D content. For example smart-phones ship with Web browsers capable of displaying rich content (i.e. images and Flash). Along another line is the growth of browser-based, virtual worlds such as Google's Lively. Whilst these technologies are currently in their infancy, it is fairly obvious that they will mature into a very capable platforms for interactive 3D experiences.

Showroom

Showroom is photo-realistic cloud rendering made available to consumers. The concept of render-farms is certainly not new, but making the technology easily available to the general public is. The current technology preview illustrates how Showroom can efficiently render dynamic, photo-realistic scenes 'on-demand'. Conventionally this processor intensive work has been conducted on a desktop computer, tying up CPU cycles and requiring installation and maintenance of complicated rendering software. By moving this task into Showroom not only are CPU cycles freed but the software and materials libraries used can be far more sophisticated. The end result is that cloud-based rendering may prove to be faster and of a higher quality compared to its desktop counterpart.

Why the need for change?

Autodesk is a financially profitable company that dominates many of the software sectors it competes in. Why is there a need to branch out into cloud-based computing, especially when success of these initiatives may in the long-term harm their conventional, desktop business?

Moore's Law can't keep up when it comes to 3D

Nothing has reinforced the limitations of working with 3D data on a desktop computer more than my time spent teaching CAD and rendering to architecture students. Experienced digital modellers gain a subconscious understanding of the processing limitations of their desktop computer. However, like children learning about gravity the hard way, those starting out with 3D do not have the same appreciation for these boundaries. Consequently the most challenging part about teaching students how to create effective 3D models and renderings is not the creation of geometric data, it is getting them to stop. The problem is once introduced to the concept of CAD, (or more recently BIM) students have an uncontrollable urge to model every screw and light-fitting. No matter whether this was five years ago on a Pentium 3 or today with a Core2 Duo, students will do their best to overload the available hardware through simple, blissful ignorance.

"Google is like lots of PhDs driving tanks. It is all about brute force - everyone is General Patton. They don't drive around the wall, they drive through the wall. It is dumb techniques used in large scale."

Adam Bosworth

Database Requirements in the Age of Scalable Services (13:04-13:18)

MySQL Users Conference 2005

Google Earth was the first mainstream demonstration of the power of integrating a vast online 2D/3D data-store with the interactivity of a rich client interface. However as far as processing went it is very simple. Digitally representing the Earth down to the individual building is made possible because the only data downloaded and rendered by the client is what can be 'seen' on-screen. This is fine for basic, macro-level visualisation but it does not work for a richly detailed Building Information Model (BIM). In this environment AEC professionals need the ability to digitally represent all aspects of the design - from its 3D properties down to the thermal characteristics of the materials. To make effective design decisions this potentially infinite data-set needs to be right at hand. As a result the challenge facing Autodesk is not just to store the underlying data in the cloud, but also the entire, 3-dimensionally realised model so that it can be efficiently navigated, manipulated and simulated.

Breaking existing vendor relationships with on-demand services

Unlike traditional desktop software an online offering will allow Autodesk to compete head-to-head on competing vendors 'home turf'. Currently the AEC sector is a patchwork of companies each committed to a particular CAD/BIM software vendor. This is primarily due to the licensing and training costs associated with this business critical functionality, but the vendors do their bit by making their products 'more compatible' with their own offerings. If deployed in an open and ubiquitous manner, Autodesk's Internet strategy could overcome these business firewalls by enabling Autodesk-centric functionality to be embedded into competing products. For example consider the following scenario:

John is developing a building model in Microstation, his architecture practice's primary BIM tool. He likes the work-group capabilities of Microstation but wishes that it had better tools for demonstrating to the client what the building will look like in its urban context. On a whim (and without "I.T's" approval) he signs up for an Autodesk.com account and installs the Microstation plug-in so that his model can be loaded into a very large Metropolis model of the city. He then emails the client with a link to a Dragonfly web-viewer that lets them see his building design within the context of the city within their Internet browser. They are really impressed and ask if they could see some renderings of the building from the street at different times on day. As the model is already in Metropolis he takes the plunge and requests some Showroom renders using the most trusted material definitions found on Seek. He is told that the renderings will take some time to complete so he goes back to working on his Microstation model. Within minutes he receives an email from Showroom to say that his renderings are ready. The quality of the results are more than enough to impress the clients, but the practice's part-time renderer/animation guru says he could have done better if there was the budget to upgrade to the latest version of his rendering software (and a faster computer). Overall John is more than pleased with the result, especially considering instead of a large upfront expense his account was billed as he chose to use the services on offer. He could see that even though the practice was not going to migrate from Microstation anytime soon, they were going to use Autodesk's online services more often in the future.

Reaching new customers and markets

After twenty-odd years of fierce competition in the CAD software space the battle-lines are fairly well defined. The Google Earth/SketchUp combination has demonstrated there are vast, untapped reserves of potential customers for 3D tools in unconventional sectors, developing economies and the casual market. Unfortunately trying to sell $1000-$5000 software to people who do not recognise the value, cannot afford the license fees or do not want to pay is an impossible mission. Cloud-based computing can potentially overcome these barriers through its ability to scale and be delivered to users at low cost.

The proven results of this cloud-centric strategy can be seen in the success of Google and SalesForce.com. Both companies have been able to enter markets previously inaccessible to traditional vendors, and simultaneously undermine the position of the well-entrenched competitors in existing, developed markets.

For example:

- Google's online advertising (AdWords) gives anyone the ability to advertise and undermined the position (and cost structure) of conventional advertisers.

- SalesForce.com uses a Software as a Service (SaaS) model to deliver feature-rich Customer Relationship Management (CRM) services to a broader audience and at considerably lower costs than traditional alternatives.

- Google Apps is providing a suite of business services to educators, non-profits and small-businesses at zero cost whilst undermining the unquestioned dominance of Microsoft's Exchange/Office suite in larger corporations.

Autodesk the Software + Services company

A business strategy that includes online services diversifies Autodesk's income stream and protects it from any downturn in its traditional product offerings. The ability to sell additional services to users enables the up-front cost of the software to be lowered on the assumption that lost income will be recouped over the life cycle of the product. This provides a competitive edge over software vendors who's sole income is from the software's initial sale. This lower up-front cost in turn helps make the desktop software more palatable to a broader audience.

This "shavers and razors" approach is certainly not a new business strategy, but it has not yet been exploited within the AEC software industry. It would not be unreasonable to suggest that if Autodesk's Software + Services strategy were to successfully mature, high cost items such as Revit could be sold at a significantly lower rate (currently a Revit subscription is US$725 per year, per user). The mobile phone market uses this model to great effect, so much so that even Apple have adopted it in order to ship more iPhones.

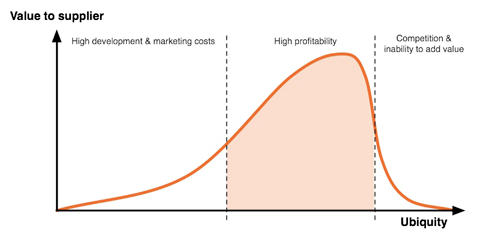

An observation on ubiquity: The part of most value in a 'stack' rises as the components below become ubiquitous

Ubiquity is a powerful yet dangerous asset for a business. Ubiquity drives adoption and product sales which leads to healthy profits. On the other hand ubiquity results in imitation and a stifling of innovation due to the momentum of legacy. Reaping the rewards of ubiquity is the goal of any software company, but escaping its pitfalls is a harder and often undervalued proposition.

"..nobody who was an ice harvester became an ice factory, and nobody who was an ice factory became a refrigerator company, and nobody who is a refrigerator company is investing in biotechnology. Because most people stay on the same curve. Better saw... more horses.... bigger ice factory... more colours of refrigerator.

Very few people have the courage or vision to get to the next curve."

Guy Kawasaki

The Art of Innovation (17:25-17:55)

MySQL Users Conference 2007

Autodesk illustrated great foresight in its acquisition of Revit on the cusp of the Building Information Model's 'tipping point'. The purchase was also timely because it preempted the demise of AutoCAD as their venerable "cash cow". We can confidently state that AutoCAD is on the way out for three reasons:

- Competition: There are now many low-cost and free alternatives on the market that do an excellent job of 3D CAD. Thanks to OpenDWG these competitors can read and write AutoCAD files.

- Lawsuits: Any company that needs to resort to suing the competition to maintain an edge in the market is destined to loose out in the long-term.

- Ribbons: The introduction of a 'ribbon' interface as the primary feature for any software release is a clear sign that its designers are clean out of useful functionality to add which justifies the upgrade cost.

Unfortunately for Autodesk nobody can be quite sure whether Revit will become ubiquitous, and if it does how long its time will last. This initiation of a bold Internet strategy acts as a safeguard to these uncertainties. Not only would a successful suite of Internet services reinforce Revit's hold on the BIM market, but it also allows Autodesk to "get to the next curve" before the competition.

Learning from and living on Amazon's cloud

Whilst it is early days yet, the thinking and implementation of this Internet strategy has no doubt been shaped by Amazon's suite of cloud computing web services. Not only are the services offered by Autodesk hosted on Amazon, but the manner by which functionality has been compartmentalised is very similar to Amazon's architecture.

The very existence of Amazon's services has enabled Autodesk's cloud-centric strategy to be launched with relatively little investment. Only a couple of years ago such a project would have required in-house development of a compute cluster. This expensive proposition becomes very difficult to justify when moving into uncharted business waters. In contrast, the flexibility offered by today's 'pay as you go' compute services from Amazon, Google and others enable clusters to be setup in a matter of minutes at extremely low cost ($0.10 per CPU hour on EC2). A significant and very attractive property of these rented compute clouds is their linear pricing model. This greatly simplifies business models for companies like Autodesk when choosing to build services because there is no cost penalty for success. In contrast choosing to build on a traditional infrastructure does not guarantee cost effective scale. This runs the risk of breaking the business model (operating at a loss) or failing to meet demand (momentum loss) as the service becomes popular.

It will be interesting to see how closely Autodesk follows Amazon's delivery model for these services. Currently the emphasis is on exposing functionality through Autodesk's own desktop and web products. However the opportunity exists to follow Amazon and publicly expose the underlying, low-level services to external developers via a set of for-pay web service APIs. Amazon followed this exact path in the release of their cloud-based web services stack, and what started off as an internal project soon flourished into a multi-million dollar industry. If things play out in a similar manner it is not unreasonable to suggest that one day the rendering engine of ArchiCAD could be Autodesk Showroom, or that Microstation models may happily co-exist next to legacy AutoCAD ones in a Metropolis cluster.

The effect of open source (or you can teach an old dog new tricks)

It is somewhat ironic that for Autodesk, an icon of the proprietary software world, the key enabler of this Internet strategy is open source software. Open source forms the backbone of the virtualisation technology (EC2 is based on Xen) and the host images that run on top of it (currently Linux and OpenSolaris). The freedom provided by the various open source licenses which make up this software stack enable its massive scale. This open source foundation is now beginning to extend beyond the virtualisation layer and is seeping into Autodesk's own programming practices. For example Seek is built on top of Java and makes use of many open source libraries such as Lucene and Spring. Whilst this is not a sign that a Linux version of AutoCAD will be released tomorrow, the acknowledgement by Autodesk that open source is a valid development model is a promising first step.

No plan survives contact with the enemy

Grand thoughts of a cloud-centric Autodesk are nice to postulate, but the reality is in the real world things are not so clear cut. In many ways the group behind this strategy is the Autodesk equivalent of Apple's Macintosh Pirates of 1983. Like the now infamous Macintosh developers, the group is small, intentionally isolated from the mothership and proposing products that may fundamentally shake up the tried and true business model (in this case desktop CAD/BIM). Whether or not such a promising start is allowed to blossom will not simply rest on the ability of the team to execute, but also the response they get from "old school" Autodesk and its competitors as this promising plan unfolds.

What will the "old schoolers" have to say about this?

For any online strategy to be successful it must be fully supported by the traditional software products offered by Autodesk. This goes well beyond the current (minor) integration that currently exists, to a point where venerable desktop products such as AutoCAD, Revit and Max are completely reshaped to take advantage of the possibilities on offer. Such an undertaking is not a simple task, especially when product managers have conventional feature requests to address and limited resources on hand.

Well beyond this practical matter is the degree to which a paradigm shifting Internet strategy can be successfully communicated within a software behemoth. For the Internet strategy put forward to take hold and flourish a significant portion of Autodesk's 7,000+ staff will need to comprehend and fully support the idea. Furthermore this clear sense of direction needs to come from the top and flow through the company in a similar manner to Bill Gates' 1995 'Tidal Wave' memo. This now infamous directive refocused all of Microsoft's software efforts to exploiting the Web's potential at a time where it could have been superseded by others. What is promising is that Autodesk's current CEO, Carl Bass, led the Buzzsaw team so he obviously understands the Internet and does not need to experience a Gates-like "eureka" moment.

Even if the concept is well communicated and Autodesk's desktop offerings are remodelled there is still the question of how internal divisions will react when their sales numbers are impacted by competing, cloud-centric products. For example taken to their ultimate (hypothetical) conclusions Showroom (rendering) and Dragonfly (modelling) will perform tasks well enough that for a subset, or even majority, of users the purchase of traditional desktop clients like Max and AutoCAD becomes unnecessary. Internal management structures within large companies are always fractured and at war with each other, so when this happens one of four things occur:

- The new, competing product is terminated (the old guys win).

- The new product is hamstrung or merged with a division that cannot manage it properly (the old guys win but the boss doesn't tell the new guys).

- The existing product is put out to pasture (the new guys win).

- The two products begin competing against each other and loose out to a third party (both guys loose).

There are many cases were internal competition over the same user-base has lead to conflict. Perhaps the most famous example brought to light recently was the 2001 internal struggle within Microsoft between Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer over the future of NetDocs, an Internet-based, Office competitor. The end result of this conflict was that NetDocs was unofficially cancelled, handing Google a lead in the online productivity market which Microsoft may never recover.

Concluding thoughts

Autodesk are making some bold moves when it comes to the Internet. Whether or not these initiatives will be allowed to mature and foster a healthy user-base is another matter. Time to market is crucial, not only will it preempt competition but it will also act as a very clear sign of the company's overall intentions. For the good of the industry we are all hoping that services like Seek, Showroom, Dragonfly, Metropolisis and their competitors flourish. Whilst picking a winner at this early stage is impossible, the mere fact that that CAD and BIM is about to make that 'one small step' from the desktop to the cloud can only lead much bigger (and hopefully better) things.